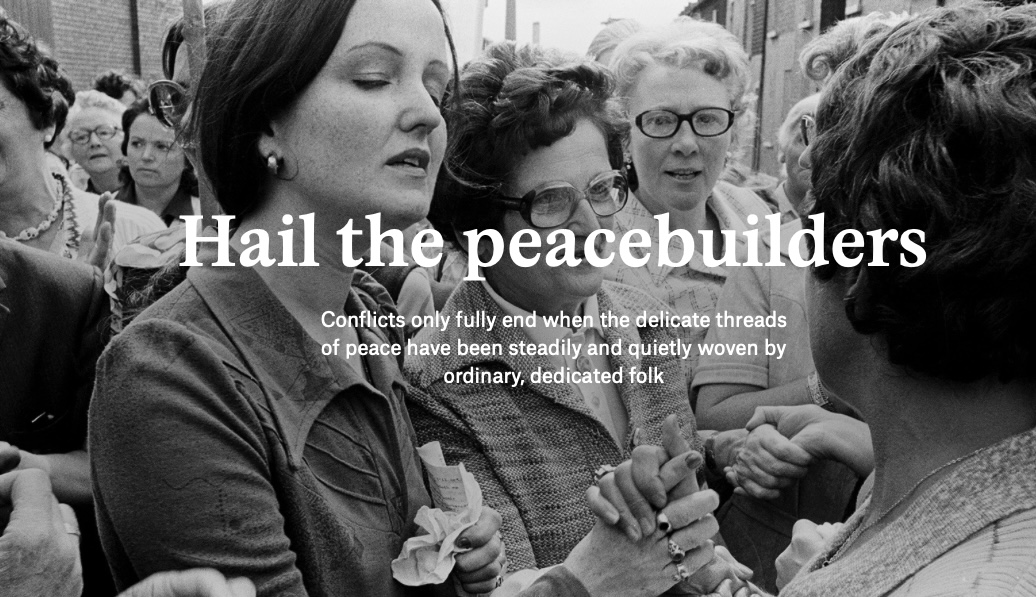

25 years of the Good Friday Agreement

24/04/23 15:57

A short article by Siobhán Haire - Deputy Recording Clerk of Britain Yearly Meeting

Most people over the age of about 35 with a connection to Northern Ireland will remember the Good Friday Agreement being signed. I do. I grew up just outside Belfast and at Easter 1998 when the Agreement was formalised I was 12 years old, on a canal boat somewhere in England. I wasn't blessed with keen political insight, but even I dimly grasped that what I was hearing on the radio was important.

For all that, I certainly wouldn't consider myself an expert on the Agreement, the Troubles, or contemporary Northern Ireland. I'm at least 10 years too young for the first, 20 years too young for the second and I haven't lived full-time in Northern Ireland for nearly two decades. But my teenage years were immeasurably safer and more normal than those of my parents, largely because of the Agreement and the work which led up to it.

I've watched that period and the build up to it fictionalised through the (excellent) TV show Derry Girls. I can't watch the episode which focuses on the referendum where Northern Irish people overwhelmingly voted for peace, without a bit of a cry at the optimism of the characters, buoyed up and overcoming their personal misgivings.

A post-conflict society?

Northern Ireland has changed enormously since 1998. Airport security is less of a hassle, people no longer just travel there to visit family or go on black taxi tours of Troubles flashpoints and the Irish language is much more in evidence across all communities. In many ways, it's a post-conflict society.

But that's not the whole picture. Although day-to-day life is much more normal in Northern Ireland than it used to be, it's still a place whose political system is not really working, where members of the police service have good reason to be vigilant about their personal security, and which is a constant headache for its near neighbours.

So what does Northern Ireland's journey in the last 30 or so years teach us about peace?

Building relationships

It teaches us that personal relationships and trust build the conditions for peace. The key relationships between the politicians – Northern Irish, British, American, who negotiated the agreement, are well documented. But the necessary relationships weren't just between the star players.

Harking back to Derry Girls again, one of the absolute truisms of the programme is that as a young person growing up in Northern Ireland in the 90s, you were never more than a few metres away from some sort of cross-community youth initiative to get to know the 'other side', (whichever side that might be). Some of those programmes were supported and hosted by Quakers at Quaker Cottage where for decades, Friends and others patiently built relationships, held space, and witnessed to the common humanity of people on both sides of the peace walls.

Towards a lasting peace

It teaches us that peace is fragile, and dependent on the political and social conditions in which it is rooted. While the first 18 years post-GFA generally felt like a steady march away from violence and towards a lasting peace, the seven years since the Brexit vote have rocked that sense of progress. Political intransigence has shaped the years since 2016, with Stormont suspended for almost 4 of the last 6 years, and a slow creep of violence and threat coming out from the shadows.

It teaches us that peacebuilding is a job for patient and persistent optimists. If you look at civil society peace movements in Northern Ireland – and there were many – there's a good argument that they were at their strongest in the late 1960s to the mid 1980s, not the 1990s when the Agreement was finally signed. This isn't to negate their impact, only to say that it didn't bear immediate fruit. And if you look at the timeline leading up to the Agreement, it is full of twists and turns, ceasefires, cessations, changes to political leadership, people making and breaking commitments. Peace grows slowly.

A peace process

It also teaches us that insecurity is a barrier to compromise. The Good Friday Agreement was achieved in a situation where moderate unionism was a more dominant political identity, and where those moderate unionists felt sufficiently brave to enter into a power-sharing arrangement with nationalist parties. In the last few years, unionist protestantism has come more under threat as it becomes the political identity for a smaller segment of the Northern Irish population, and that security which gave politicians the confidence to seek compromise appears to have eroded.

There's no neat ending to this article, just as there is no neat ending to the political journey in Northern Ireland. Peace is a process requiring investment – the investment of money, of personal capital and of time. Are we working to encourage investment in a peaceful future for Northern Ireland?

THE PEACE TESTIMONY - AFTER MEETING CONVERSATION

12/12/22 22:20

After Meeting for Worship on Sunday 11th December 2022, a group of Friends met to consider the Quaker Peace Testimony. To stimulate discussion, the session began with a conversation between Will Haire and Honor Stewart (for the full text see attached file) We wondered if the testimony was articulated clearly and what it might mean. The nature of war has changed over the centuries, becoming increasingly deadly, destructive and all-encompassing. The role of Quakers has evolved too: not only do they continue to promote peaceful alternatives to armed conflicts, but they are also active in providing humanitarian aid, in supporting peace-making and reconciliation efforts, and in diplomacy, especially by their presence at the United Nations. We recognised the challenging nature of some circumstances, especially relating to self-defence and employment. Being at peace is not just about stopping war, but is also about trying to remove the causes of war and in developing good relationships at all levels. A ‘Just Peace’ broadens the concept of peace to include ideas of social and economic justice and ecological sustainability. The nature of security could be reframed to focus on meeting human needsrather than on military strength. We considered how our Peace Testimony might relate to our daily lives and what role education might play in creating a more peaceful world. Finally, we were reminded that peacemaking can be seen as a natural outworking of the life of the Spirit.

South Belfast, After Meeting Conversation @ 11 Dec 2022

The Quaker Commitment to Peace

Introduction from Will

We are here today to talk about the Peace Testimony.

For long we have done so in South Belfast mainly in the context of the Troubles. But now we do so in the context of the invasion of the Ukraine. So many of us are wondering what we can say in that context. Honor is a member of the IYM Peace Committee, and has been thinking a lot about these issues, so she and I thought it might be useful to have a dialogue about this, and to draw the rest of you into this conversation.

Question 1: So first Honor, what do you see as the “Peace Testimony”, and indeed, what does Testimony mean in this context?

First, I’d like to comment on the word ‘testimony’. I am not a birthright Quaker; rather I came to Quakerism ‘in later life’! I was drawn particularly to the unprogrammed style of Quaker worship and also to the values that Quakers seemed to espouse. In the religious tradition in which I was brought up, the word ‘Testimony’ was used more in the sense of a person testifying to their experience of personal ‘conversion and salvation’. So, I learned that Quakers used the word ‘Testimony’ in a different way. It seems to me, that Quaker testimonies are values that members seek to live out in their daily lives.

Although, initially, I was particularly interested in ideas of Equality and Integrity, I knew of some of the roles, particularly peace-making, that Quakers undertook in the context of various conflicts. As Will says, more recently I’ve been giving the Peace Testimony a lot of thought, and indeed, I suppose the war in the Ukraine has brought this particular testimony much more into the minds of many people.

So, I suppose, initially, I saw the Peace Testimony in much the same way as the other testimonies, as a personal commitment - in this case to strive for a peaceful disposition in myself. But I was also aware of the wider contexts (particularly international or tribal) where one would be opposed to killing and war. However, I think there’s more to it than that, which we’ll come on to … and which I’m still trying to figure out!

Question 2: Is there one clear statement that all Friends have adhered to?

To me, it does NOT seem so - which can be a bit confusing!

One the one hand, there seems to a view that Testimonies are not set in stone; rather, over time, and with discernment, the interpretation of them might evolve, and new ones might emerge (such as the more recent ones of Community and ecological Sustainability or Stewardship). On the other hand, some people have talked to me about THE Peace Testimony, as if it was something written down and to which many people seemed to subscribe. Indeed, I was told that THE Peace Testimony WAS written down and some people sent it to me. I asked if the other testimonies (Equality, Simplicity, and Integrity) were written down too, and was told that they weren’t! Confused!

I realised that THE Peace Testimony, a version that was written down, referred to what George Fox said to King Charles II in 1660. In the context of the English Civil War, when there had been rebellion against the monarch, I wondered what Fox actually meant at the time. He is quoted as saying that his ‘Quakers’ sought peace, denied all bloody principles and practices, and that they would never ‘fight and war against any man with outward weapons, neither for the kingdom of Christ, nor for the kingdoms of this world’. By saying that, was he reassuring Charles that his group, his ‘Quakers’, had no intention of taking up arms against the king, perhaps unlike other religious groupings which were emerging at the time? Or was he saying something more timeless, that, for example, under no circumstances should one kill or take up arms? The latter interpretation would seem to be more in keeping with the Quaker view of Equality and the idea that ‘there is that of God in everyone’.

Recently, in the notices which Inge circulated, there was a statement signed by Tim Gee, General Secretary of FWCC (Friends World Committee for Consultation) and by some other national or international Quaker organisations. Since then, I’ve listened to Tim being interviewed about that statement, and he talked about how challenging it was for those (Quaker) organisations to reach agreement about the text. So, finding a form of words, particularly one which will not be misunderstood, is not necessarily straightforward. He also said, “The Peace Testimony constantly evolves … with every major conflict people have to struggle with it and work out what they are called to do.” And he added, “In its foundation, it is a WE statement, about what WE are called to do,”

Question 3: Has that changed over time, as warfare has become more deadly, more all encompassing, involving all society?

I think it has. War has changed, and Quaker responses/activities have evolved.

Life appears to have become much more complex since the 17th century. We live in a world which is more interconnected and interdependent – what happens in one part of the world can have consequences around the globe, and quite quickly – as we’ve seen with the conflict in the Ukraine. Modern weapons have unimaginable power and can have such devastating consequences. A weapon strike can be initiated remotely, being set off in one country and landing in another. Some strikes are targeted with great precision, others are indiscriminate; and the use of artificial intelligence, drones and nuclear weapons moves combat onto whole new levels. In these sorts of circumstances, it is difficult to see how defence forces could be confident that their actions would meet a standard which required that there be no lethal consequences (no killing).

Such warfare can cause death and injury on a large scale, widespread destruction of infrastructure, a ravaging and a pollution of the environment, and a waste of eye-watering amounts of money which could be spent in more constructive ways. In these conflicts where people are not safe, and lack food, clean water, shelter and sometimes heat, there is an inevitable displacement of the population. Especially when people cross national or tribal boundaries in large numbers, there can be resentment from established populations, with competition for resources, and further conflict can break out.

In the centuries since the English Civil War, Quakers have not just refused to fight or to take up arms. I don’t use the word ‘just’ with any disrespect; rather, Quakers have been called to additional spheres of work and influence. We can think of the courage it took for men to be conscious objectors in WWI and the derision and imprisonment they endured as a consequence. Or think of the bravery and compassion of those in the Friends’ Ambulance Unit in WWI and WWII.

Quakers now work to relieve the suffering of people injured or displaced, and support refuges in many settings. They have become involved in trying to prevent conflicts, and in trying to negotiate settlements. Although Quakers are well-known for their work in peace-making and reconciliation, they often work in quiet ways, behind the scenes, and are trusted to do so. Quakers are more involved now in diplomacy, and through our Quaker Office at the United Nations we speak out on the world stage about peace and injustice, all the while promoting peaceful alternatives to armed conflict.

War is brutalising, it tends to escalate, and is usually futile, leaving communities with resentments and long memories. Eventually, warring sides must be brought together if peaceful and lasting settlements are to be reached. How much better it would be if they did that in the first place.

Question 4: What does it mean if innocent groups are still attacked? Do we believe that there are absolutely no circumstances where the use of some violence can be “just”?

I’m not sure. There was a quotation used at Yearly Meeting this year at Stranmillis, suggesting that Isaac Pennington took a slightly different stance to that taken by Fox, in the same era. Whilst he too looked to a better time when ‘nation shall not lift up sword against nation; neither shall they learn war any more’, he nonetheless did NOT seem to speak against people who defended themselves against foreign invasion or who used a weapon (a sword) to suppress violent and evil-doers within their borders. Indeed, he said that using the sword could be honourable, when borne uprightly (whatever that might mean!).

He also suggested that the hoped-for better, peaceful, future state must begin with individuals – which I thought was interesting. It relates to what I’ll be mentioning later.

I think it’s a tough question to answer, whether it is right/appropriate to defend oneself, maybe even using physical force, when confronted with imminent, and possibly lethal, danger. Is there a right to self-defence? As it was put so poignantly at IYM at Stranmillis, if a family member is about to be brutalised, would you stand by or intervene? That question begs other questions, such as: if you would defend your family, would you defend your neighbour, and who is your neighbour?

In that same interview, Tim Gee said, “We are a people who follow after peace, love and unity, and we pray that other feet will follow in the same path.” He also said that it’s not about asking, ‘What would I do if I was someone else?’ Rather, it’s about asking, “What is God asking me to do, as whom I am, right now, in the place that I’m in?”.

With regard to a Just War, the rules of engagement are said to include being able to distinguish between combatants and civilians. Also, in response to any attack, actions should be proportionate. In the face of modern military armaments, it’s difficult to see how those criteria could be met.

Question 5: Is it perhaps that our focus should be on a “Just Peace”, that will attack the roots of war, before it ever can start?

I think there needs to be a shift in two paradigms: the one from discussions of a ‘Just War’ to those about a ‘Just Peace’; and the other in relation to security.

One description of a Just Peace suggests that it has at least four dimensions:

a. Peace IN the community (local)

b. Peace IN the marketplace (economy)

c. Peace WITH creation (ecological/environmental)

d. Peace BETWEEN nations (international).

This description of a Just Peace usefully broadens our concept of peace to include ideas of social and economic justice and ecological sustainability. If we work for greater justice in those areas, areas from which conflict can stem, we might be tackling some of the roots of war. Given the widening gap between the rich and the poor, and the human contribution to climate change and loss of biodiversity, it is obvious that there is much work to be done.

Thinking of peace in these terms also requires/enables us to rethink what we mean by security. Arguably, none of us can feel secure as long as others do not feel secure. If the annual expenditure on armaments (which is currently around 2 trillion dollars) was diverted towards achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals, we could, for example, do wonders in combatting poverty, preventing violence, avoiding disputes over resources, and protecting the planet. This desirable approach requires a shift in security policy from that which is military-based (depending on the strength and equipment of a country’s armed forces) to one which focuses on real human needs (sometimes called ‘Human Security’).

Question 6: How have Quakers thought about creating a peaceful world?

Quaker Testimonies are commitments to behaving in certain ways; they should lead to actions.

Creating a peaceful world can’t just be about preventing war, hugely important though that is. There has to be another dimension to it too, which I think is about creating positive relationships.

I think there’s the macro and the micro, the big picture and the more local.

I’ve already touched on some of the actions that Quakers are already taking to prevent or to end war, such as: their humanitarian and diplomatic work, through peace-making and reconciliation activities, through campaigning to relieve poverty, and being active in the environmental movement. Other people campaign against the arms trade. If we are personally not active in these areas, we can support others who are; for example, this meeting supports CAAT financially.

I was on a Zoom call last year about the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. A Jewish lady, from Machsom Watch (they monitor military checkpoints) was speaking. She was asked how we could help. She said, “Raise your voice”.

I’ve mentioned some of the roots of war. Other causes include: a response to a perceived wrong committed (such as a retaliation to an invasion); a perceived ‘good end’ (such as regime change); attitudes of covetousness, seeking power, conquest, glory or feeling insecure. I’m not sure how you deal with all of those, but part of the answer may be to do with education.

International warfare is not something that many of us have to deal with in our day-to-day lives … at the moment! However, the ‘Peace in Community’ dimension of a Just Peace IS more immediate for us, because conflict is part of life. It is more obvious in circumstances such as street riots or domestic violence, but it is also present in squabbles within families or between neighbours, bullying in schools, and in our inability to disagree, or to make a point, respectfully and calmly (think politicians, or social media!!).

There was a shocking statistic in Friday’s Irish Times: in the RoI, “Gardaí are responding to a report of domestic abuse or violence every 10 minutes, with almost 50,000 complaints made to the force this year and many more offences continuing to go unreported.”

The PSNI have launched their first Action Plan for Tackling Violence against Women and Girls. (I know that men are abused too, but this plan happened to be about females).

What do those two reports tell us about society on our own doorstep?

Some peace organisations are doing work on gender roles and behaviours. (E.g. Conciliation Resources, ‘Integrating Masculinities in Peacebuilding: Shifting Harmful Norms and Transforming Relationships’).

Quakers in Britain have recently published an impressive report entitled ‘Peace at the Heart - a relational approach to education in British schools’. It presents peace education as a comprehensive approach to teaching and learning that puts good relationships – peace – at its heart.

The report identifies four complementary aims;

1. Individual wellbeing and development (Peace with myself; Taking care)

2. Convivial peer relations (Peace between us; Working together)

3. Inclusive school community (Peace among us; Coming together)

4. The integrity of society and the earth (Peace in the world; Taking a stand).

There is evidence that such a relational approach brings many benefits, including the fuller development of young people, emerging citizens who are more consciously involved in their society. They have developed qualities and skills (such as empathy, confidence, attentive listening, critical thinking & leadership skills) and learned ways of dealing with conflict (such as acknowledging & handling emotions, or using peer mediation and restorative practices) which they will carry with them into adulthood. These young people may become, or influence, future leaders of society or future peacemakers.

Last Sunday, Felicity spoke here about the Quaker Integrity Testimony. She reminded us that testimonies are relevant for our daily lives. I think the Peace Testimony should be too.

And peacemaking can be seen as a natural outgrowth of the life of the Spirit.

If I may, I’d like to finish by reading a paragraph from The Guided Life, by Craig Barnett, which some of us were discussing on Wednesday evening in the Book Group. (Page 56):

“The capacity to understand and forgive is essential to resolving conflict in our daily lives. In our families, communities and workplaces conflicts and resentments often wear away at people because they are never resolved or reconciled. Each of us, through our daily relationships, can contribute to bringing understanding and reconciliation to those around us. Instead of feeling resentment and blame, simply listening to others without judgement is a powerful source of peacemaking. By speaking truthfully and acting with kindness and integrity, people from every background are sources of continuous healing in their communities. The gift of everyday peacemaking is a fruit of inner faithfulness to the life of the Inward Guide, the Seed of insight and understanding.

So, what does love and my/your commitment to peace say to, or require of, me/you today?

Question 7: Now can we throw this open to everyone - what does the Peace Testimony mean to you, and how do you feel you have to live it out?

Faithfully maintaining our testimony against war

12/05/22 12:35

On 6 March the national, representative Quaker body, Meeting for Sufferings, gathered in worship. Oliver Robertson shared this prepared ministry on the complex web of issues as major armed conflict has arisen again in Europe.

Friends, let us hold in the Light the people of Ukraine. Let us hold in the Light the people of Russia. Let us hold in the Light the people of Afghanistan. Let us hold in the Light the people of Ethiopia. Let us hold in the Light the people of Myanmar. Let us hold in the Light those affected by conflicts we have forgotten or have never even heard of, because the consequences of war will scar lives just as they are doing in Kyiv. Let us hold in the Light the people working for peace. Let us hold in the Light the people who are not.

Prayer can be a great comfort, and a powerful spur to action. But what will comfort us and what will comfort others may be very different. We need to hear the voices of people affected by today's wars, so that their lived experience can help us better understand how God is leading us in that situation. But whose voices are we hearing? Pay attention to the news you notice and the events that move you, as it can be a window into your priorities and your prejudices.

Making connections

So how do we connect with people living close to armed conflict? During worship last weekend, one meeting put up on their walls the names of Russian and Ukrainian peacemakers. Many Friends have joined the online meetings for worship of Quakers in Kyiv, and of Friends House Moscow, which has been quietly building peace since the end of the Cold War. Whose voices should we be raising up? Which stories should we be challenging?

Oftentimes taking a pacifist stance, of faithfully maintaining 'our testimony that war and the preparation for war are inconsistent with the spirit of Christ', is itself a challenge to a dominant narrative. Its value is often to remind people that there is another way, that even when war may seem the only answer there is still a choice and an alternative.

Nonviolent resistance

That alternative is not passivity. Friends and others have long experience of nonviolent resistance. People may nonviolently demonstrate, as thousands of Russians have been this past week, and being arrested for it – including children. People may refuse to support occupiers, both passively – such as not going to work – and actively – such as damaging the weapons they are forced to make. Many of the most powerful acts of nonviolent resistance manage to both challenge the oppressive action and assert the humanity of everyone involved. When Syrian protestors gave flowers and water to soldiers, it showed both that they were not a threat (so making it harder to shoot them) and meant that the soldiers could see them as people like themselves. Such actions are not about victory over an enemy, but about turning an enemy into a friend.

Upholding people

One of the ways Quakers have often acted on our conviction that we are all God's children, that everyone has value and worth, is to support the people shunned by others. This can be about practical support, and it can also be about reminding the rest of the world that these are people too.

When I think of the people who may be shunned, I think of conscientious objectors. It will take some considerable courage to be a conscientious objector to military service today in Russia and in Ukraine, though for different reasons. Quakers have long upheld the right to refuse to kill; how can we support those who are holding firm to that stance even in the most trying circumstances? Would we support COs who come to Britain? If we didn't, are we confident others would?

When I think of people being shunned, I think of those people fleeing Ukraine who are not white. People of colour in Ukraine, students from Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, have been reported to have been hampered or attacked as they tried to flee, denied support and accommodation in Ukraine and neighbouring countries because they are not Ukrainian. How can we support them, and in so doing uphold the notion that all refugees should be treated equally?

And when I think of people being shunned, I think of Russians around the world. It's probably very lonely being a Russian in a lot of countries right now. Are we helping to ensure that any outrage over the Russian government's actions does not turn into hatred of all Russians, those with no links to the government, no influence over its actions?

Opportunities for action

Many of us may be feeling, that's all well and good, sharing stories and holding in the Light and so on, but what can we actually DO? How can we stop the bloodshed or at least mitigate its impacts?

We may be able to give money, to give time, to offer hospitality, to undertake relief work, to use our resources and our riches as individuals and as communities. But the reality is that the role we can play from here in Britain, at this time of war, may be more limited than we would like. Friends may be familiar with the hourglass model of peace work, where there is space before war and after war to carry out many actions for peace, but at the time of conflict itself, where the hourglass pinches in the middle, there is very little opportunity.

There can sometimes be a temptation to think of what great thing we can do, on a par with the times past when Quakers organised the Kindertransport or advised the Russian Tsar. But those things could only happen because of groundwork being done, relationships being built, for years beforehand. Have we built the foundations we need for such work today? Has someone else, so that our role is to support? We aren't necessarily called to be amazing. We are called to be faithful.

Building the commonwealth of heaven on Earth

One of the things we can get from our faith and our long-established testimony against war is a clear vision of the world we want to see, the divine commonwealth that God is calling us to live in. Some of the greatest strides towards that world have come after very dark times. What are the changes that are needed? What work do we need to do now to clear the way for such changes to happen? What are the existing institutions and practices that need to be celebrated and maintained, even if they are imperfect? What would need to happen for Russia's neighbours not to see it as a threat? What would need to happen for a military alliance in Europe to feel unnecessary?

As Paul Parker was quoted last month, "war today is the failure of yesterday that leads to unimaginable human suffering on all sides. Imagine what could happen if we were willing to invest as much in peace as we currently do in preparing for war."

Just imagine Friends. Then let us get to work.

(Taken from BYM website - Written by Oliver Robertson - Head of Witness and Worship for Quakers in Britain)

Read more about Quaker responses to war in Ukraine

Friends, let us hold in the Light the people of Ukraine. Let us hold in the Light the people of Russia. Let us hold in the Light the people of Afghanistan. Let us hold in the Light the people of Ethiopia. Let us hold in the Light the people of Myanmar. Let us hold in the Light those affected by conflicts we have forgotten or have never even heard of, because the consequences of war will scar lives just as they are doing in Kyiv. Let us hold in the Light the people working for peace. Let us hold in the Light the people who are not.

Prayer can be a great comfort, and a powerful spur to action. But what will comfort us and what will comfort others may be very different. We need to hear the voices of people affected by today's wars, so that their lived experience can help us better understand how God is leading us in that situation. But whose voices are we hearing? Pay attention to the news you notice and the events that move you, as it can be a window into your priorities and your prejudices.

Making connections

So how do we connect with people living close to armed conflict? During worship last weekend, one meeting put up on their walls the names of Russian and Ukrainian peacemakers. Many Friends have joined the online meetings for worship of Quakers in Kyiv, and of Friends House Moscow, which has been quietly building peace since the end of the Cold War. Whose voices should we be raising up? Which stories should we be challenging?

Oftentimes taking a pacifist stance, of faithfully maintaining 'our testimony that war and the preparation for war are inconsistent with the spirit of Christ', is itself a challenge to a dominant narrative. Its value is often to remind people that there is another way, that even when war may seem the only answer there is still a choice and an alternative.

Nonviolent resistance

That alternative is not passivity. Friends and others have long experience of nonviolent resistance. People may nonviolently demonstrate, as thousands of Russians have been this past week, and being arrested for it – including children. People may refuse to support occupiers, both passively – such as not going to work – and actively – such as damaging the weapons they are forced to make. Many of the most powerful acts of nonviolent resistance manage to both challenge the oppressive action and assert the humanity of everyone involved. When Syrian protestors gave flowers and water to soldiers, it showed both that they were not a threat (so making it harder to shoot them) and meant that the soldiers could see them as people like themselves. Such actions are not about victory over an enemy, but about turning an enemy into a friend.

Upholding people

One of the ways Quakers have often acted on our conviction that we are all God's children, that everyone has value and worth, is to support the people shunned by others. This can be about practical support, and it can also be about reminding the rest of the world that these are people too.

When I think of the people who may be shunned, I think of conscientious objectors. It will take some considerable courage to be a conscientious objector to military service today in Russia and in Ukraine, though for different reasons. Quakers have long upheld the right to refuse to kill; how can we support those who are holding firm to that stance even in the most trying circumstances? Would we support COs who come to Britain? If we didn't, are we confident others would?

When I think of people being shunned, I think of those people fleeing Ukraine who are not white. People of colour in Ukraine, students from Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, have been reported to have been hampered or attacked as they tried to flee, denied support and accommodation in Ukraine and neighbouring countries because they are not Ukrainian. How can we support them, and in so doing uphold the notion that all refugees should be treated equally?

And when I think of people being shunned, I think of Russians around the world. It's probably very lonely being a Russian in a lot of countries right now. Are we helping to ensure that any outrage over the Russian government's actions does not turn into hatred of all Russians, those with no links to the government, no influence over its actions?

Opportunities for action

Many of us may be feeling, that's all well and good, sharing stories and holding in the Light and so on, but what can we actually DO? How can we stop the bloodshed or at least mitigate its impacts?

We may be able to give money, to give time, to offer hospitality, to undertake relief work, to use our resources and our riches as individuals and as communities. But the reality is that the role we can play from here in Britain, at this time of war, may be more limited than we would like. Friends may be familiar with the hourglass model of peace work, where there is space before war and after war to carry out many actions for peace, but at the time of conflict itself, where the hourglass pinches in the middle, there is very little opportunity.

There can sometimes be a temptation to think of what great thing we can do, on a par with the times past when Quakers organised the Kindertransport or advised the Russian Tsar. But those things could only happen because of groundwork being done, relationships being built, for years beforehand. Have we built the foundations we need for such work today? Has someone else, so that our role is to support? We aren't necessarily called to be amazing. We are called to be faithful.

Building the commonwealth of heaven on Earth

One of the things we can get from our faith and our long-established testimony against war is a clear vision of the world we want to see, the divine commonwealth that God is calling us to live in. Some of the greatest strides towards that world have come after very dark times. What are the changes that are needed? What work do we need to do now to clear the way for such changes to happen? What are the existing institutions and practices that need to be celebrated and maintained, even if they are imperfect? What would need to happen for Russia's neighbours not to see it as a threat? What would need to happen for a military alliance in Europe to feel unnecessary?

As Paul Parker was quoted last month, "war today is the failure of yesterday that leads to unimaginable human suffering on all sides. Imagine what could happen if we were willing to invest as much in peace as we currently do in preparing for war."

Just imagine Friends. Then let us get to work.

(Taken from BYM website - Written by Oliver Robertson - Head of Witness and Worship for Quakers in Britain)

Read more about Quaker responses to war in Ukraine

The Artform of Peace Building

14/06/21 18:57

A really wonderful article on peace building with many mentions of Quakers and familiar Quaker and Quaker adjacent names like Diana and John Lampen, Duncan Morrow and Paul Hutchinson

https://aeon.co/essays/peacebuilding-is-an-artform-crafted-by-divided-peoples

Prof John Paul Lederach in conversation with Dr Gladys Ganiel

04/02/21 12:14

Reflecting on peacebuilding, conflict resolution and reconciliation

The Senator George J. Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice at Queen’s University hosts Professor John Paul Lederach of the University of Notre Dame (USA) ‘In Conversation’ via Zoom with Dr Gladys Ganiel (QUB). Lederach, an internationally acclaimed expert in conflict transformation, will reflect on the most significant advances in conflict transformation over the course of his career; his own research and practice; religion and reconciliation; and the prospects for peacebuilding in Northern Ireland and further afield. Ganiel’s research specialises in religion, conflict and reconciliation.

This is an event related to the 4 Corners Festival organised in partnership with the Senator George J Mitchell Institute, QUB.

In Memory of Joan Huddleston

23/01/20 09:11

Today would have been Joan Huddleston's 80th birthday. Joan was one of the original co-founders of this website and worked tirelessly to produce material for it and provide guidance and support to the rest of the website team. One of the aspects of the site that Joan took full responsibility for was sourcing materials for the Musings from a Quaker Bonnet section. The series ran for 77 months, so there is a wealth of material from the old version of the site that we plan to gradually move to the new site, and no better time to start that than on Joan's Birthday. Joan would have often ministered in Meeting for Worship on the subject of peace, which was a testimony very close to her heart. If feels appropriate for this reason to start with the following Musing.

Peace begins within ourselves. It is to be implemented within the family, in our meetings, in our work and leisure, in our localities and internationally. The task will never be done. Peace is a progress to be engaged in, not a goal to be reached.

Sydney Bailey

How Much Are We Spending On The Military?

14/08/19 22:40

For further details on the content of this info-graphic go to https://howmuch.net/articles/the-worlds-military-spending

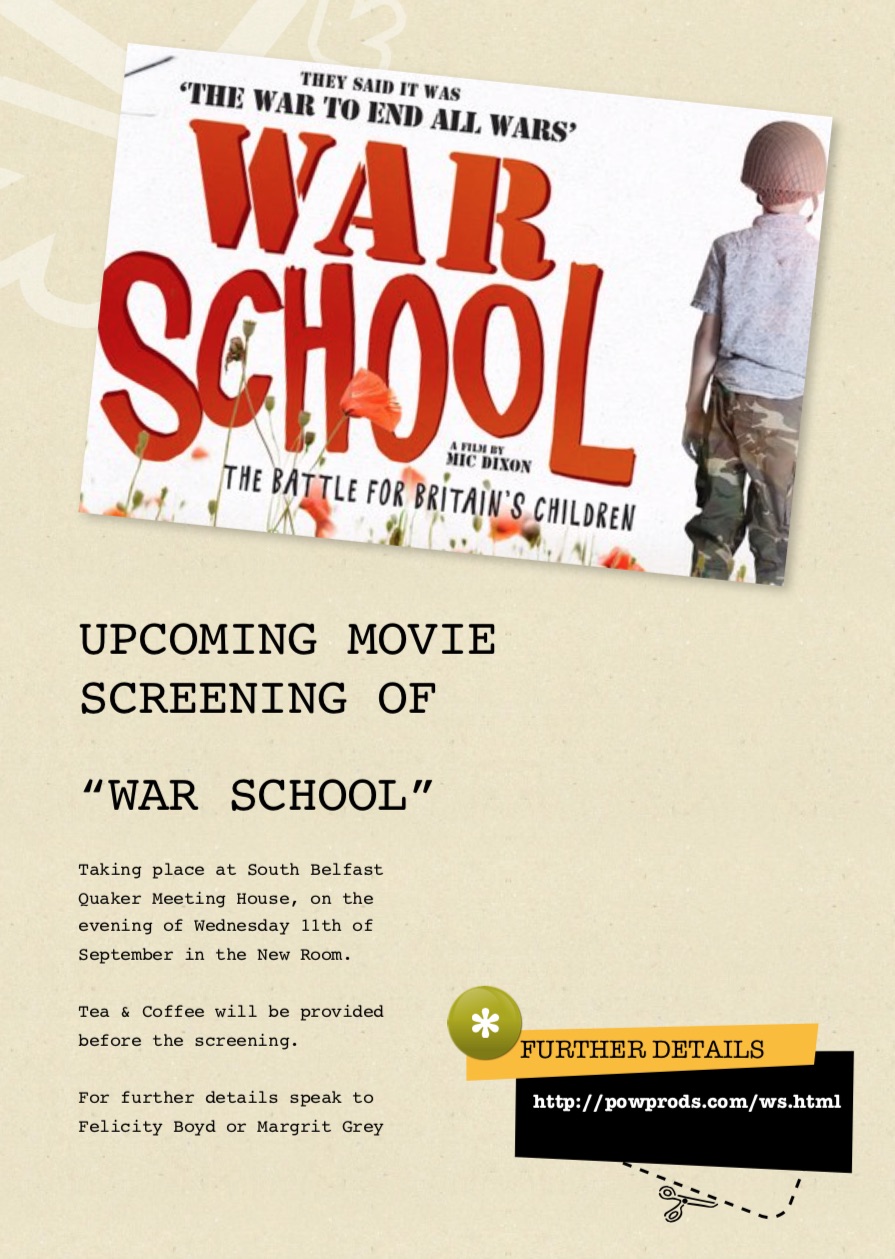

War School Screening @ The Meeting House

09/08/19 21:25

War School is a film about the battle for the hearts and minds of Britain’s children.

Set against the backdrop of Remembrance the controversial and challenging documentary reveals how, faced with unprecedented opposition to its wars, the British government is using a series of new and targeted strategies to promote support for the military. Armed Forces Day, Uniform to Work Day, Camo Day, National Heroes Day - in the streets, on television, on the web, at sports events, in schools, advertising and fashion – the military presence in civilian life is on the march. The public and ever younger children are being groomed to collude in the increasing militarisation of UK society.

Interweaving the powerful and moving testimonies of veterans of Britain’s unbroken century of wars with expert commentary, archive and a redolent score, War School’s mosaic of sound and imagery evokes the story of the child soldier who becomes a peace campaigner, challenging the myth of Britain's benign role in world affairs and asking if perpetual war is really what we want for future generations?

http://powprods.com/ws.html

Tea and Coffee served from 7:00pm Movie starts at 7:30pm

Campaign Against Arms Trade

18/06/19 19:54

Dear friend,

WE HAVE BIG NEWS. THIS THURSDAY AT 10AM, A VERDICT IS DUE TO BE ANNOUNCED ON OUR APPEAL AGAINST THE SALE OF ARMS TO SAUDI ARABIA.

UK policy clearly states the government must deny licences if there is a ‘clear risk’ arms ‘might’ be used in ‘a serious violation of International Humanitarian Law’. In spite of hundreds of alleged breaches of International Humanitarian Law, the government has supplied more than £5 billion of arms to Saudi Arabia since the conflict in Yemen began.

We feel hopeful that the Court of Appeal will agree these sales were in fact unlawful. Whatever the result, the worlds media will be watching, and we must use this moment to force change. Government must follow their own rules on arms sales, or rip them up and start again, because theyre not worth the paper theyre written on.

JOIN US AS THE NEWS BREAKS ON THURSDAY MORNING AT 10AM

Follow us on Twitter (https://crm.caat.org.uk/sites/all/modules/civicrm/extern/url.php?u=3645&qid=1812553 or Facebook (https://crm.caat.org.uk/sites/all/modules/civicrm/extern/url.php?u=3646&qid=1812553 , or if you can, come down to the Royal Courts of Justice on and be one of the first to know the result.

WHERE: OUTSIDE THE ROYAL COURTS OF JUSTICE (https://crm.caat.org.uk/sites/all/modules/civicrm/extern/url.php?u=3647&qid=1812553 , STRAND, LONDON, WC2A 2LL. NEAREST TUBE/RAIL: TEMPLE, BLACKFRIARS, HOLBORN.

If you cant follow the news on Thursday, well let you know the result by email as soon as we can.

Whichever way this goes, I want to take this moment to thank you for all that you've done over the last four years as we've fought this legal battle together, for every email you've written or donation you've made. Without your support, this work simply couldn't happen.

https://crm.caat.org.uk/sites/all/modules/civicrm/extern/url.php?u=3638&qid=1812553

In solidarity

Caroline

CAMPAIGN AGAINST ARMS TRADE